Conservation through Creative Writing

To view the photo-rich magazine version, click here.

Originally appears in the Fall 2018 issue.

RECENT RESEARCH has shown that narrative structure has a powerful impact on the human brain. Studies in neuroscience and narrative structure support this idea; some researchers are finding that narrative structures such as those used in fiction and poetry can have a much stronger impact than simple facts; when we read or hear the sensory details of someone else’s experiences, we respond to them neurologically as if they were our own experiences.1 Furthermore, studies have found that when reading literature with important messaging about behavior, students have begun to engage in more positive behaviors as suggested by the literature read in classes.2 Other areas of criticism such as feminist theory and Marxist theory have helped to raise awareness about how narratives can maintain oppressive structures, but there hasn’t been much discussion about how narratives can either reinforce or reinvent our relationships with animals.3 Moreover, it has been said that the ecological crisis that we are facing today will not be solved through science and technology,4 and there has been a growing interest in using the humanities to tackle these challenges.

This research provides educators with new opportunities to explore both narrative writing and ecology as means of building literacy skills, meeting Common Core Standards, and potentially impacting how students and their communities view their relationships with animals and the environment. Anecdotally, I have found that students become more engaged in writing lessons that focus on animals, and though I am an English teacher, I imagine that giving students an opportunity for creative expression may help those who struggle with ecological and biological studies in the science classroom.

In the last few years, I have experimented with and researched ideas for different activities in the secondary classroom. I would like to share some of the more successful lessons I have used so that other educators can explore them with their students. While these lessons were designed with high school students in mind, I think they could easily be adapted for middle and upper elementary grades.

Lesson 1: A visit to the zoo

A visit to the local zoo is always exciting for students. Being able to see animals in action and learn about conservation through an in-person experience is incredibly valuable. But how do students make this learning their own? How do teachers lock in these experiences for students? Adding a creative writing component may offer students a way to dive deeper into what they learn. Zoos are ripe for this sort of interdisciplinary learning; many zoos already have poetry installations throughout their exhibits. In fact, five zoos across the United States have partnered with various organizations and poets-in-residence to create intentional poetry installations: New Orleans, Louisiana; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Little Rock, Arkansas; Jacksonville, Florida; and Brookfield, Illinois.

At one high school where I worked, all sophomore students visited the Brookfield Zoo as part of their biology class. While chaperoning this outing, I realized that there was a huge missed opportunity to involve other disciplines in the trip, especially since the biology work that students needed to complete did not take the whole day. While working with Brookfield through my graduate program, I had the opportunity to design a curriculum that could be used for such a trip. While this curriculum was designed particularly for Brookfield, many zoos now feature poetry throughout their exhibits, and these activities could easily be adapted for other zoos or natural history museums.

Preparing for your visit

Preparing for your visit

One of the last things that your students will be expecting to find at the zoo is poetry, but if you are hoping to provide them with a rich, interdisciplinary experience, it may be a good idea to prepare them prior to coming.

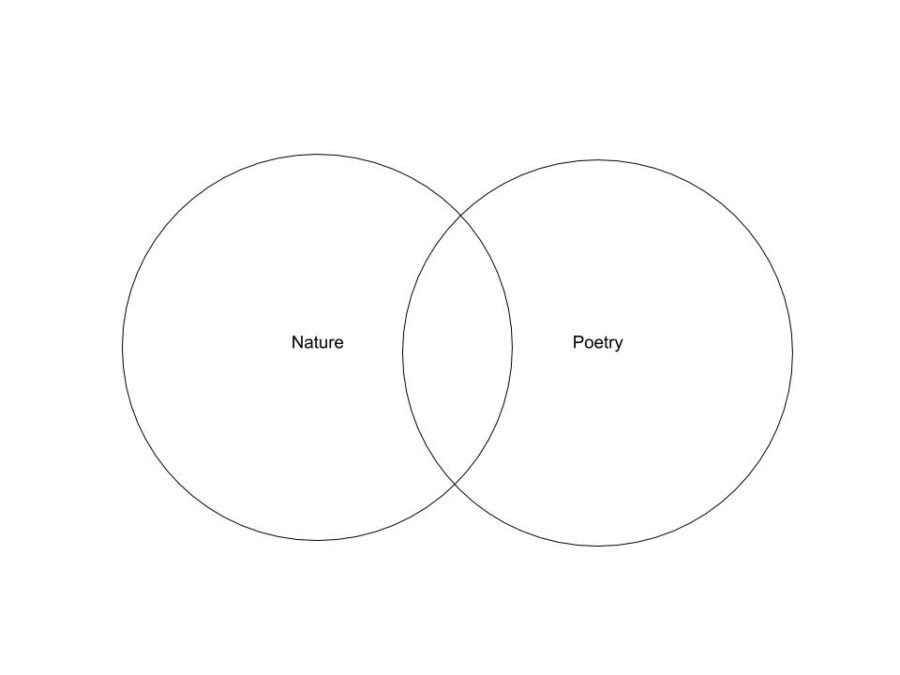

One way that might be useful to help prepare students would be to find out how they feel about both zoos and about poetry. They will likely have strong feelings about each (It has been my experience that students either love or hate poetry, but usually become very excited to learn about nature.), but probably have not considered how the two may work together. Try creating a Venn diagram on the board or on chart paper with the word “poetry” in one circle and the word “zoo” in the other. (“Nature” would also work well here if you want them to think more broadly about these terms.) Have students volunteer their feelings about each term, and when you have a wide range, you can encourage them to fill in the middle section if no common terms came up when you were discussing each term independently.

Now that the students are thinking of these terms collectively, explain that when you visit the zoo, you will encounter poetry while you are there.

While at the zoo

Have each student choose an animal about which they want to learn more. You can allow students to develop their own questions, prompting them to learn more about the animal that they have chosen. The following list contains suggested questions, but I’m always amazed by what students can generate on their own:

What is its habitat like? Where does it come from?

What does it eat?

What interesting behaviors does it have?

What is its role in its ecosystem?

What is its conservation status?

Is there anything that we can do in our communities to help this animal?

While you are observing, what do you notice about the animal?

Does the animal remind you of anything else?

Back in class

After searching for poetry at the zoo, students will hopefully be hungry to write their own poems. For some students, the fun of this activity will be in having a chance to write something their way. Teachers can offer criteria to include, such as describing the animal’s habitat, ecological niche, and conservation threats, but some students may need more structure. The following two examples provide formats for poems that are both easy to follow and easy to adapt based on particular learning criteria, such as descriptions of the animal, their diet, habitat, or threats to their population.

Acrostic Poem: a poem in which the first letter of each line spells a word vertically down the page; usually the word is also the subject of the poem.

Polar Bear

Pelt thick and white as the snow,

Over your black skin that soaks in the sun

Loving the water, you dive in

Applying your skills,

Raking your claws over the sides of a seal

Beautiful as you are frightening,

Everyone in the tundra fears you,

Ashore you hunt less, eat bearberries

Rare, endangered beast

A diamante is a seven-line poem, shaped like a diamond.

Line 1: one word

Line 1: one word

(subject/noun) that is contrasting to line 7

Line 2: two words

(adjectives) that describe line 1

Line 3: three words

(action verbs) that relate to line 1

Line 4: four words (nouns)

first 2 words relate to line 1; last 2 words relate to line 7

Line 5: three words

(action verbs) that relate to line 7

Line 6: two words

(adjectives) that describe line 7

Line 7: one word

(subject/noun) that is contrasting to line 1

These forms can help students who struggle with poetry. Students who feel stifled by forms might work a little outside of the directions, as in the diamante below, which doesn’t quite follow the form:

Polar Bear

Hunter, Swimmer, Diver

Lives in the cold, arctic

Eats seals, lemmings

Snow white fur

Endangered

Lesson 2: Portrayals of animals

What if traveling to a zoo isn’t a realistic option? Perhaps there’s no funding for buses or planning a field trip is too logistically challenging. Maybe there just isn’t a zoo within a reasonable distance from your school.

The following unit sketch, designed for high school English teachers who are looking to increase engagement in writing and exploring themes of conservation with their students, can take place entirely in the confines of the classroom and school day. It also allows teachers to either expand on past lessons about criticism or to introduce the idea of literary criticism to students. This is also an opportunity for cross-disciplinary work in both science and English classrooms.

Step One: Activating Prior Knowledge

Many students are familiar with the film The Lion King. As a result, classes could view a few short excerpts from the film to help stimulate a discussion: How are animals portrayed in the film? Are these portrayals accurate to how these animals are in real life? How does the film show anthropomorphism? Do these portrayals contribute to positive or negative images of these animals?

Step Two: Exploration

Give students homework to record animals in literature and popular culture through the week. Have them record these in their journals by making a table. Students will inform what should be recorded and how to record data, but here is an example of how the table could look:

| Animal | Where observed? (name of book, television show, movie, product commercial, etc.) | Does animal appear in positive or negative way? (p/n) | Does the animal have human traits? List them. | Additional observations |

Students will enter their data into a Google Docs sheet that will be used to compile all student data. In this way, students will have a large sample size with which to work.

Step Three: Data Analysis and Research

Students can examine the results and identify the top five poorly or misrepresented animals. These animals will be divided among five groups in the class. In their groups, students will research the animals. Each group will learn about their animal’s behavior and ecological niche, and they will look for more examples of the animal in literature and popular culture. A possible field trip to the zoo will allow students a chance for experiential learning.

Step Four: Narrative Component

Students will then individually create their own narratives in order to express a story that is authentic to their animal and that may encourage conservation behaviors in readers. Our students followed the YWP “Young Writers Program” NANOWRIMO (National Novel Writing Month for young writers) model as previously used in class. Available on their website is a standards-aligned workbook for teachers to use with student writers to help them learn about narrative structure while drafting their own stories. Although November is National Novel Writing Month, these materials can be used year-‘round, and there are options for both secondary- and elementary-aged students.

Step Five: Community storytelling event

When students have completed their stories, why not give them a real audience? Students can plan an event and invite members of their communities to hear their stories. This could take place at the school, or maybe there is a location nearby that would be willing to host. Coffee shops are often open to readings or maybe your school has a garden; using such a space could help engage the community in both the students’ stories and nature at the same time.

Conclusion

These suggestions are just a collective starting point for bridging science and creative writing. When I was forming these ideas, I was thinking about myself as a student. As a young writer, I was fascinated by nature and science, and despite understanding the concepts, I struggled with the products that I needed to prove my understanding of them. For years, I labeled myself as “bad at science,” and it wasn’t until long into adulthood that I allowed myself to “try” science again. Perhaps if we find new ways to engage students, we can make science accessible to all learners and build a larger army of young conservationists.

Resources

The Association for the study of literature and the environment, www.asle.org

This website contains a wealth of resources for teachers and conservationists interested in bridging conservation and the humanities.

NANOWRIMO Young Writer’s Program, www.ywp.nanowrimo.org

This website contains a variety of tools for teachers interested in teaching narrative writing. These resources can easily be adapted for teaching different themes or content.

Footnotes

Zak, P. (2013, December 17). How stories change the brain. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain

Rominger, P. E., & Kariuki, P. (1997, November). How children’s literature affects positive social behavior of third grade students at a selected elementary school. Paper presented at the annual conference of Mid-South Educational Research Association, Memphis, TN. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED413598.pdf

Shapiro, K., & Copeland, M. W. (2005). Toward a critical theory of animal issues in fiction. Society & Animals, 13(4), 343-346. doi:10.1163/156853005774653636

White, Lynn. 1974. The historical roots of our ecologic crisis. In D. Spring & E. Spring (Eds.), Ecology and religion in history, New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Elizabeth Joy Levinson lives, teaches, and writes on the west side of Chicago. She has an MFA in Poetry from Pacific University in Oregon and an MAT in Biology from Miami University. Her poetry has appeared in several journals, including Grey Sparrow, Up the Staircase, and Apple Valley Review. Her chapbook, As Wild Animals, is available through Dancing Girl Press.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.