Green Buddhism

To view the photo-rich magazine version, click here.

Originally appears in the Spring 2022 issue.

By John Negru

Editor’s Note: A major focus of our running Finding Common Ground sub-series has been to see where environmental education overlaps with different faiths and spiritual practices. This article serves as a primer to Buddhism, namely the practice of Green Buddhism. With this knowledge in tow, we encourage you to seek opportunities to incorporate Green Buddhism into your learning and teaching.

Buddhist basics

Shakyamuni was a prince who abandoned his life of privilege to find answers to life’s fundamental questions in India more than 2,500 years ago. His quest involved six years of intense spiritual practice, culminating in Enlightenment after a night deep in solitary meditation. For the next 40 years of his life, he walked all over northern India, explaining what he had discovered and leading growing communities of like-minded seekers.

India in those days was well-acquainted with wandering ascetics, gurus, yogis, adepts, and sundry forest-dwellers. In that sense, Shakyamuni’s quest was well within the Hindu cultural norms of that time as well as agrarian culture. What made him unique was his approach to spiritual life, a life of moderation that came to be known as The Middle Way. He rejected the theism of his Hindu roots, its caste system, and its ritualism. He also rejected asceticism.

This was a pre-literate society, with strong oral traditions. Although Shakyamuni, who came to be known as the Buddha — the Awakened One — gave thousands of teachings and led countless retreats during his lifetime, nothing was written down until hundreds of years after his passing. The Buddhist Canon comprises an enormous number of texts and commentaries, none of which has much primacy over the others within each category.

Buddha was more interested in solving the root of suffering than in discovering the origins of Creation or having a relationship with a god or gods. In Indian cosmology, the Universe cycles through beginningless and endless evolution. It’s important to understand that context, since Western cosmology, until very recently, was premised on a linear view of time, with teleological implications.

You might say Shakyamuni Buddha took a pragmatic look at the nature of his experience and the world around him and observed three fundamental tenets:

- Impermanence. Nothing lasts forever. In fact, nothing lasts at all except in the most provisional of ways. We only have this present moment. Life is a causal sequence of ephemeral sense data combined with the narrative we tell ourselves to make meaning of it.

- Interbeing. There is no independent, inherently existent, eternal soul. We do not exist separately from our fellow life travellers or environment. Like waves in the ocean, beings and events arise and subside in dependent arising. We need a systems approach to understand reality.

- Suffering. When we hang on to labels or expectations, tell ourselves a false narrative about our experience or the world around us, and cling to the sense of a separate self, we suffer. Birth, old age, sickness, and death are facts of life, but they are not the ultimate sources of our suffering. Those can be attributed to our ignorance, greed, and hatred. We are sleepwalking, oblivious to the wondrous miracle of our shared life. This misunderstanding is at the root of our suffering.

His entire message was an elaboration on four basic Truths: the reality of suffering, its cause, its cessation, and the eightfold path to achieve that liberation. Buddhism is not a religion of faith, ritual performance, or adherence to commandments. Nor is it about accumulating spiritual merit. Indeed, one might say Buddhist practice never saved anyone and one might not even need to identify as Buddhist while practicing Buddhism. On the contrary, it is a contemplative practice that focuses on waking ourselves up by cultivating calmness, reducing the distractions of our sick consumer society, being mindful of what is actually happening with each breath, and nurturing more positive mental states. Out of this calm abiding and insight arises great compassion.

The essential foundations of Buddhist practice are the Five Precepts:

- Don’t kill.

- Don’t steal.

- Don’t lie.

- Don’t be sexually irresponsible.

- Don’t take intoxicants.

With education and meditation, we can build on these ethical foundations, living in a manner that is mature, harmonious, and non-harming to others. Our True Nature is luminous but hidden from us by our own misguided attempts to achieve happiness by accumulating more things, controlling more people, turning a blind eye, or lamenting what we think fate has dealt us.

That’s pretty much it.

The evolution of Buddhist teachings (the Dharma)

The evolution of Buddhist teachings (the Dharma)

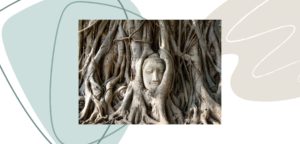

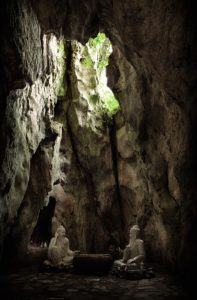

Down through the centuries, as Buddhism spread across Asia and into the West, it has taken on a great variety of forms. As different lineages became institutionalized, a great flowering took place. The first two residential universities in the world, Nalanda and Taxshila, were Buddhist monastic organizations created in the 5th century; they operated for more than 750 years. Over generations during the 8th and 9th centuries, Buddhist communities created temple complexes of great architectural and engineering accomplishment, such as the Ajanta Caves in India, Borobudur in Indonesia, Angkor Wat in Cambodia, and the Dunhuang Caves in China.

In what is known as the first Turning of the Wheel of Dharma, as Buddhism died out in India, it spread to Southeast Asia (Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand), with an emphasis on Buddha’s original teachings, community structures, and mindfulness meditation. This tradition is known as the Theravada, the Way of the Elders. A great text in this lineage is The Dhammapada.

In the second Turning of the Wheel, Buddhism spread to China, Korea, and Japan. There it became infused with Daoist and Confucian principles and became known as the Mahayana, the Great Way. Mindfulness meditation became more intimately connected with being in nature. This was also the crucible for the development of Ch’an Buddhism, which later evolved in Japan into Zen. The emphasis in Zen is on direct experience of reality, an iconoclastic rejection of scholasticism. Buddhist meditation became something for everyone, a much more inclusive perspective for laypeople than one where their sole role is to support their ordained brethren in the cloister or subservience to an authoritarian political system. A great text in this lineage is The Mountains and Rivers Sutra, by Dōgen in the 13th century.

In the third Turning, Buddhism encountered the shamanistic societies of the Himalayas and evolved into what is known as the Vajrayana — the Way of the Thunderbolt — with its dynamic techniques of visualization and meditation to create the mystic energy needed for inner awakening and transformation. A great text in this lineage is The Jewel Ornament of Liberation, by Gampopa in the 12th century.

All these lineages and traditions have found their way to the West. There are more than 600 Buddhist organizations and communities across Canada, and thousands more in the United States. You can find Buddhist groups all around the world; it is truly a global religion. But if you were to visit several of them, even in the same city, you would find that they may barely resemble each other in terms of what they think, say, and do.

Engaged Buddhism: a new way

Buddhism arrived in the West in the late 1800s, but it was not until the 1960s that Buddhism really entered into Western culture with lots of Western practitioners. This was a time of great social evolution and civil rights movements, student protests, and openness to new ways of structuring our relationships. It was also a time of increasing secularization, as illustrated by Québec’s Quiet Revolution.

In 1950, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, who drafted India’s Constitution, and who was a co-creator of modern India with M.K. Gandhi, converted to Buddhism along with hundreds of thousands of Dalit (Untouchable) class Hindu citizens in a non-violent re-visioning of Indian society.

During the Vietnam War, a young Vietnamese monk called Thich Nhat Hanh became involved in social activism and came to the West to promote another way forward based on Interbeing and deep ecology, known as Engaged Buddhism. His work and lineage have profoundly transformed all branches of Buddhism.

Green Buddhism

Green Buddhism

Buddhism is fundamentally about seeing “reality” as it really is. This may have been interpreted as an individual hero quest in the past, but for us — here, now — it encompasses facing the climate crisis, extinctions, pollution, and destruction of our planet through our own misguided extractivism, consumerism, and materialism. It’s an “all-hands-on-deck” situation.

Buddhist practice is an evidence-based investigation, a systems approach that is entirely congruent with modern scientific methods, but without the naïve belief that science is always objective or that technology is the solution to all our problems. You could say that Green Buddhism is Engaged Buddhists’ response to the reality of planet Earth in the Anthropocene, looking for the causes of the suffering and figuring out how to resolve them as expeditiously as possible. Indeed, Shakyamuni Buddha was frequently referred to as The Great Physician.

The diagnosis: human overshoot has caused us to live beyond our planet’s means. If you read Limits to Growth, by Donella Meadows et al. back in the 1970s, or if you’ve shown your students movies from the Story of Stuff Project by Annie Leonard, or if you’ve seen the art of Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, you knew this was coming.

The remedy: Regenerative environmental design and a sustainable socio-economic structure, based on a new value proposition.

Back in 1973, Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered, by E.F. Schumacher, was the first popular book to present what Buddhist economics could look like in the modern era. In 2017, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, by Kate Raworth, updates Schumacher’s model with both overshoot boundaries on the outer edge and social equity shortfalls on the inner edge of our future safe zone. Neither of these authors professes to be a Buddhist, but their paradigms are entirely congruent with a Buddhist perspective.

As Buddhists have taken up the challenges of the Anthropocene, their initiatives have taken many forms.

What does Green Buddhism look like?

On a personal level, living a simple lifestyle and eating as vegan a diet as possible have always been central to Buddhist practice. At the other end of the spectrum, in terms of political structures, the Buddhist kingdom of Bhutan has adopted a civic model of Gross National Happiness as its measure of civilizational success rather than Gross National Product and has become the first carbon-neutral country on the planet.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama was the recipient of the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize based on his environmental work, and he has been a tireless advocate for the environmental health and biodiversity of the Tibetan Plateau (the world’s Third Pole), which is the source of the great rivers of Asia and is crucial to the well-being of literally billions of people in their watersheds.

In Ladakh, the Gyalwang Drukpa recently led his 15th annual Eco Pad Yatra pilgrimage, [1] bringing environmental education services to remote villages. In India, the Karmapa’s environmental movement, Khoryug, [2] coordinates projects across many Buddhist monasteries. In Thailand (where injuring monks is taken very seriously), Buddhist bhikkhus have ordained trees to save them from illegal logging. [3]

In North America, Green Buddhist practice is young, but rapidly evolving. A lot of it is online.

For websites from Green Buddhist communities, start here:

- One Earth Sangha: https://oneearthsangha.org/

- Earth Holder Community: https://earthholder.training/

- Buddhist Global Relief: https://www.buddhistglobalrelief.org/

- Life Itself: https://lifeitself.us/

- Plum Village: https://plumvillage.org/

- Extinction Rebellion Buddhists – Global: https://www.facebook.com/groups/2166143550304582

- Ecobuddhism: https://www.facebook.com/groups/106653225660

- Rocky Mountain Eco Dharma Center: https://rmerc.org/

For articles on Green Buddhist topics, I recommend the following:

- Buddhistdoor Global (https://www.buddhistdoor.net/). They have many environmental features and columns, such as Bodhisattva 4.0, Dear Earth, or The Bodhisattva’s Embrace.

- Tricycle (https://tricycle.org/topic/society-environment/). This is the leading US Buddhist magazine, so their articles cover a wide range of topics, but they are increasingly featuring Green Buddhist content.

- Lion’s Roar (https://www.lionsroar.com/tag/environment-climate-change/). This is the leading Canadian Buddhist magazine.

Looking for books about Green Buddhist practice? Here are a few recommendations:

- This Fragile Planet: His Holiness the Dalai Lama on Environment, edited by Michael Buckley (Sumeru, 2021)

- Love for the World: Joanna Macy and the Work of Our Time, edited by Stephanie Kaza (Shambhala, 2020)

- Ecodharma: Buddhist Teachings for the Environmental Crisis, by David Loy (Wisdom, 2019)

- Green Buddhism: Practice and Compassionate Action in Uncertain Times, by Stephanie Kaza (Shambhala, 2019)

- Bodhisattva 4.0: A Primer for Engaged Buddhists, by John Negru (Sumeru, 2019)

- Dharma Gaia: A Harvest of Essays on Buddhism and Ecology, edited by Allan Hunt Badiner (Parallax Press, 1990)

The way forward: a personal note

The way forward: a personal note

Having worked in the Green Buddhist space for quite a few years now as a community organizer, publisher at Canada’s largest independent Buddhist press, author, and blogger, I’ve learned that Green Buddhism is still an outlier in the Buddhist world.

For example, in 2019 just before the pandemic hit, I launched a project to audit land use by rural Buddhist centers across North America. These properties comprise thousands of acres of wild land. Working with an ecologist and a landscape architect, I co-wrote and published a free project management template called The Buddhist Center Environmental Action Plan Toolkit,[4] which has been downloaded hundreds of times from my site. I then reached out to 108 North American Buddhist centres with rural properties, with an invitation to participate in mapping and auditing their environmental practices. I received many warm replies lauding me for my efforts but confessing to understanding and practicing very little in the way of regenerative environmental design. Unfortunately, the pandemic has put the project into suspended animation, but I hope to revive it soon.

Another challenge for Green Buddhism is a lack of interfaith action on the climate crisis and its causes. The Alliance for Religion and Conservation has closed after 24 years. There are a few other interfaith environmental organizations, such as the Interfaith Rainforest Initiative, GreenFaith, and Interfaith Power and Light, but Buddhist representation in those organizations is very limited. Many Buddhists are still functioning in the old silo mindset or focusing on the past instead of the future.

The last few years have brought the climate crisis into sharp focus for both young and old. We see the blah blah blah. This is when the real work begins. But the environmental movement and faith community leaders have failed to engage with each other to the degree we need in order to nurture the kind of fundamental values shifts necessary to break free of our current socio-economic paradigm.

Children’s television host Mr. Rogers always recommended that in any crisis we should look for the helpers. In Buddhism, those folks are called bodhisattvas. In Green Buddhist practice we call them ecosattvas. Each of us can be an ecosattva in our own community. Saving our only home for future generations is mission critical. If we fail at this, nothing else will matter.

John Negru is an actively retired Technological Education teacher, currently working for the Ottawa Carleton School Board. He also runs Canada’s leading independent Buddhist book publishing company, which offers a number of environmentally focused books. In addition, he is the author of six books and many feature articles for technical publications, as well as an award-winning graphic designer. You can find out more about him at https://www.linkedin.com/in/john-negru-b14a9713/.

References

[1] Gyalwang Drukpa, “The 15th Eco Pad Yatra, led by native His Eminence Drukpa Thuksey Rinpoche, has just kicked off…,” Facebook, August 11, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/Gyalwang.Drukpa/posts/the-15th-eco-pad-yatra-led-by-native-his-eminence-drukpa-thuksey-rinpoche-has-ju/2025333414172940/.

[2] Khoryug, 2022, http://www.khoryug.info/.

[3] BD Dipen, “Buddhist “Eco-monks” Work to Protect Thailand’s Environment.” BDG Buddhistdoor Global, August 17, 2018. https://www.buddhistdoor.net/news/buddhist-eco-monks-work-to-protect-thailands-environment/.

[4] John Negru, Paul Keddy, and Dennis Winters, The Buddhist Center Environmental Action Plan Toolkit (Ottawa: Sumeru, 2019), https://sumeru-books.com/collections/engaged-buddhism/products/buddhist-center-environmental-action-plan-toolkit.