Leaf Your Devices at Home – FREE ARTICLE

To view the photo-rich magazine version, click here.

Originally appears in the Summer 2022 issue.

By Britta Moore

Becoming blind to the presence of plants

Separation from the natural world has contributed heavily to “plant blindness”, the notion that people don’t notice, or are “blind” to plants in the environment around them. [1] Scientists attribute this phenomenon to two things: 1) Plants are generally not threatening to humans and don’t have the typical “warning” signals that animals have (e.g., a mean stare or a growl) and 2) our brains are filtering out so much information from our daily lives that the visual data we receive on plants is simply thrown away. [1] While we can clearly see the animals interacting in a habitat, plants are often viewed as passive participants in an ecosystem, still objects in the background of an otherwise active environment. In a forest, for example, one can watch the birds flying from tree to tree, the doe with its fawn grazing in a field, or a rabbit hopping to and fro in the grass. While it may not seem like it to most, plants are also active participants in their environment, constantly reacting to changes in resources so that they can survive, and their evolutionary history is full of acquired adaptations that enable them to “fight back” when needed (e.g., thorns and toxins).

Bringing plants back into the picture

We are in a strong position to lead our students into the natural spaces that are available to them and by doing so we can help them build a kinship with nature and promote a sense of stewardship for the environment. “Psychological research demonstrates that people are more likely to support conservation of species that have human‐like characteristics, and that support for conservation can be increased by encouraging people to practice empathy and anthropomorphism of nonhuman species.” [2] With encouragement, our students can practice such empathy with the plants that surround them in their local parks and green spaces, develop a drive to learn more about them, and grow to revere the plants that they once overlooked.

Our culture tends to place more value on animals than plants. Animals are more greatly emphasized in formal biological education, and studies show that people have “higher preference for, superior recall of, and better visual detection of animals compared with plants.” [2] A “published study showed that secondary level students, graduates, and a substantial portion of biology teachers, could scarcely recognize ten common wildflowers.” [3] Plant blindness has even permeated our conservation behaviors — plant conservation programs get “considerably less funding than animal conservation projects.” [2] Even more, a foundational understanding of plant anatomy, function, and diversity can prepare our students to develop solutions to “issues like global warming, food security, and the need for new pharmaceuticals.” [4] To promote plant conservation and prepare our students for a future in which they will need to work with botanical knowledge, we need to intentionally incorporate a more plant-centric curriculum. The following lesson will provide your students with hands-on experience with plants and recognition of them as valuable components of our natural world.

Protective Plants Lesson

Student objectives: 1. Students will be able to identify at least three plants that have predator defense traits and describe how those traits protect the plant from predation. 2. Students will recognize and describe the importance of plants in local ecosystems and the roles they play.

| Next Generation Science Standards adressed |

|---|

| 3. Inheritance and Variation of Traits: Life Cycles and Traits3-LS4-2. Use evidence to construct an explanation for how the variations in characteristics among individuals of the same species may provide advantages in surviving, finding mates, and reproducing. |

Background knowledge: Plant defenses

To foster empathy for plants, put yourself and your students in the “shoes” of the plant. Try to see things from a plant’s perspective. A plant’s ability to survive and reproduce relies on its ability to adapt to its environment. Predators and competition are among the major factors that influence their survival rate. Just like humans and animals, plants need to survive to reproduce and pass on their genes to the next generation. However, they are constantly under attack from predators feasting on their bodies (stems, leaves, twigs, etc.) and their “babies” (fruits), so over time they have evolved defensive mechanisms to fight back. Plant defenses are defined by their ability to increase a plant’s fitness or the successful passing of its genes to the next generation despite being preyed upon (Figure 1). [5] If, for example, a plant’s leaves are partially eaten by a deer, but the deer quickly realizes that the leaves are distasteful and doesn’t eat anymore, then that plant will be more likely than other plants who have sweet, tasty leaves to live, reproduce, and pass on its genes.

Plants have evolved a host of morphological and chemical features that enable them to limit the effects of herbivory. The most obvious traits are structural defenses:

- spinescence (thorns, spines, and prickles)

- trichomes (a protective layer of plant hairs)

- rigid leaves and stems that are difficult to chew

- sharp, microscopic particles inside their leaves and stems

Spinescence & trichomes

Spinescence is effective at deterring larger herbivores, such as elk, but is less effective against smaller herbivores like insects. Trichomes, on the other hand, are quite effective at keeping insects away by keeping them from freely moving on the plant and by preventing their eggs from sticking to the plant. Larger predators also find the hairy texture of trichomes to be unappetizing. Plants can get even more protection with trichomes that launch chemical defenses. In plants like the Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica), trichomes can secrete sticky resins or irritating and/or painful chemicals when touched, quickly scaring off any unsuspecting animal that attempts to graze on the plant.

Rigid leaves and stems & sharp, microscopic particles

Thick, hard leaves and stems are another resistance trait that plants use to decrease herbivory since the compounds that create the hardness (cellulose and lignin) are indigestible to most herbivores. These plants are of little dietary value to most herbivores and are also hard to eat, so animals do not bother grazing on them. Lastly, some plants have evolved microscopic resistant structural defenses in the form of sand- and needle-like tiny particles inside their tissues. Plants are able to do this by storing minerals from the soil such as silica or calcium and then transform them into stone-like phytoliths that wear on insect mouthparts or animal teeth. Some can even pierce mouth tissues of an herbivore or, if ingested, cause kidney stones.

Reduced visibility & chemical defenses

Other ways for plants to prevent or limit herbivory include reduced visibility and chemical defenses. Reduced visibility is a way for plants to hide from herbivores. They may do this by growing in areas that are inaccessible to or hidden from herbivores, such as cliff ledges, plateaus, or under heavy brush. Other plants have the ability to release volatile organic chemicals that mask the scent of a nearby plant that attracts herbivores, essentially hiding themselves through scent. Plants, like animals, can also camouflage themselves, like stone plants (Lithos sp.) who (you guessed it) “disguise” themselves as stones.

Finally, some plants have evolved the capability to produce chemical defenses to impede predation. For example, Woods’ Rose (Rosa woodsii) and Boulder Raspberry (Rubus deliciosus), along with all other members of the rose (Rosacea) family and Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana), contain cyanide compounds in their seeds that can kill animals that ingest them [6,7] (Figure 2). Colorado Columbine (Aquilegia caerulea) also has dangerous toxins that affect the heart and intestine, causing heart palpitations, vomiting, and diarrhea [7] (Figure 2). Many other plants, including Curlycup Gumweed (Grindelia squarrosa), Mullein (Verbascum thapsus), Locoweed (Oxytropis sericea), and Silvery Lupine (Lupinus argenteus), all contain dangerous toxins that will sicken or kill any herbivore that consumes them [7] ( Figure 3). Some specialists have coevolved to circumvent these chemical defenses. A popular example is the Monarch butterfly’s (Danaus plexippus) adaptation to counteract the toxic milky sap of the milkweed (Asclepias spp.). The monarch butterfly caterpillars not only have evolved the ability to ingest the toxin in milkweed that otherwise kills larger animals, but they can also store these chemicals in their bodies to deter predators of their own. [8]

Architecture & overcompensation

Sometimes though, not even the best defenses will keep a predator away. When plants lose their leaves, stems, or roots to a predator, they suffer a decreased ability to invest nutrients and energy into offspring because they must use their resources to grow new parts for survival. So, some plants have developed traits that permit them to sustain their fitness despite the loss of plant tissues during predation. Plants like wild tomatoes have an architecture (a canopy structure) that allows them to better utilize increased light availability following leaf damage and increase their net photosynthetic rate. [6] Other plants, like wild relatives of maize, get ahead of the problem by having significantly more shoots than a typical plant, making them more tolerant to stem damage because they have more to compensate for the loss. [9] Then there are plants like Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) that store most of their nutritional resources in their roots so that they can reallocate those nutrients to their shoots after they have been eaten or damaged or plants like Scarlet Gilia’s (Ipomopsis aggregata) that overcompensate for loss by increasing their seed production. [6]

Introduction to lesson

Plants have evolved a myriad of ways to fight back, survive, and thrive under the onslaught of herbivores; you can see evidence of this in many plants in your area. In addition to looking for plants that display some of traits previously discussed, you can find out more about the common plants that live in your community and their specific defensive traits by visiting a local nature center, searching the web, or visiting the library to find a nature guide or book on common plants in your region. There are also apps such as iNaturalist that can identify plants for you! The lesson outlined below uses plants from the Rocky Mountain region but can be adapted to include plants in your area. Ideally, this lesson would be conducted outdoors but could also be modified with samples in a classroom setting. Allowing students the opportunity to investigate and interact with the plants will enrich the multi-sensory learning experience.

Materials needed:

- Plant info cards (Figure 2) cut into individual cards

- Nature journals or notebooks for taking notes and drawing sketches of plants

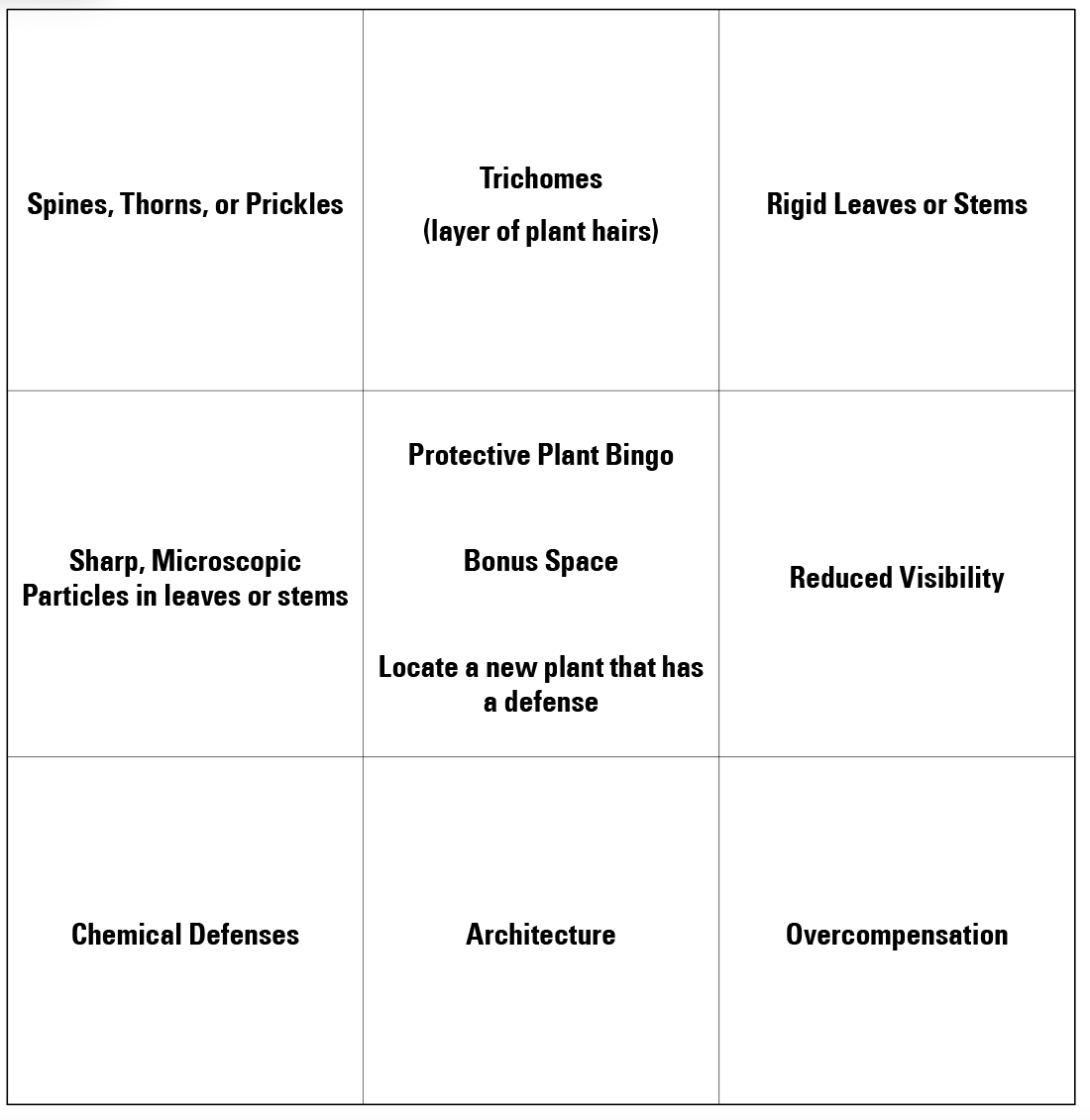

- Copies of Protective Plant Bingo Cards (Figure 3)

- Pencils

- Clipboards, binder, or other hard surface to write on outside

Instructional steps

- Before conducting the educational hike, locate the plants of focus (Figure 3) near your outdoor location of choice in order to plan stopping points for discussion. The plants used in this lesson were selected based on their abundance in several greenbelts, parks, and nature trails in and near a major city (Denver, Colorado) as well as the foothills and lower-elevation mountain areas within a short driving distance of Denver.

- Discuss safety precautions (e.g., staying hydrated; wearing appropriate weather and sun protection; staying together as a group; using the buddy system; watching out for and communicating knowledge of potential dangers such as low branches, venomous animals, or poisonous plants), as well as Leave No Trace principles (e.g., staying on the trail, packing out any trash, etc.). Discuss animals and plants that are protected in the area. You can find this by searching for your local state park website to find a list of protected plant and animal species. It’s important for you to inform participants to be especially respectful of these species and you can also use these species to illustrate the importance of Leave No Trace.

- Depending on your group size, ask participants to get into groups of two to four. Instruct them to find some nearby plants of interest to observe and provide them with the following discussion questions: What do you notice about the plants? What structures and features are common and unique among the plants? What do you think the different parts of the plant do for the plant? Have the students create lists/notes, make sketches, and write down curiosity questions. Allow 10–15 minutes for observation and note-taking/sketching.

- Reconvene the groups to discuss as a class what they noticed and what questions or insights arose as they observed and sketched the plants.

- Explain the purpose and focus of the hike: to locate plants with protective features (or defenses to predation) and to learn about how they resist or tolerate herbivory. Depending on the age group and background knowledge of your students, you may need to define terms such as predator, prey, herbivory, herbivore, and defense. Before beginning the educational hike, inform the students that there will be a competition (game) at the end of the hike to see what they have learned.

- Pass out one or two botany cards to each group (Figure 2). The Botany Cards provided can be used as a template to create your own cards for your local area. Alternatively, students can be encouraged to research local plants with defensive traits ahead of the hike and create their own botany cards in the classroom to use on the hike before carrying out Steps 3 and 4 of the lesson.

- Ask each group to choose a reader that will read the cards to the whole group once the plant is located.

- Lead the group to the previously scouted areas on the trail to the focus plants. At each plant, after identifying the plant, ask the readers to read about the plant to the group.

- Through verbal instruction, highlight the plant’s defensive trait(s). Ask the students the following: How might we identify this plant? How would you describe it? Encourage keen observation and provide guiding questions to elicit detailed descriptions of the plant. Encourage children to sketch the plant and take notes on the names, defining visual traits, and protective features of it. Before leaving the plant, ask the group these summative questions: What is the name of this plant again? What defense does it use?

- Ask the students to look for visually apparent traits such as structural defenses (thorns, spines, or prickles). Tell the group to be on the “lookout” for any other plants that exhibit this trait (if able to be seen or known by previous knowledge). If a participant sees a new example plant, or has a question about a different plant’s defense, encourage curiosity by asking them to call out their sightings or questions. Ask students what they think eats these plants to see if they make connections between the defensive structures and the type of animal it deters. Ask students if they have any ideas about how some animals may protect themselves from plant structural defenses (e.g., how can they get around the defenses to still eat the plant). Reward their participation and interest with phrases like, “Good eye! You found a rose! And you noticed that it has thorns to keep its predators away!” Encourage further participation and discussion from the rest of the group by drawing them in to see the newfound plants.

- Once all ten focus plants are located and their defenses are discussed, locate a new area of the trail and pass out the “Protective Plants Bingo Cards” (Figure 4) and pencils to the participants. Challenge the children to locate at least one plant that exhibits each defensive trait on the card. When they locate the plant, they can ask another student or their teacher to approve them to cross out the box. The goal is to cross out all boxes on the Bingo card and the first student (or small group) to get all crossed out, wins a prize. A bonus box is awarded to a student who finds a new plant that was not explicitly taught with the original 10 plants but still exhibits a defensive trait.

Modifications and add-on activities

The information cards can be edited for content to suit multiple age levels: primary, lower-elementary, upper-elementary, and middle/high school-aged children. They can be as simple as having the name of the plant along with a picture of the plant for children who are not yet reading. For older students, a more inquiry-based approach could be appropriate, where the students research plants before embarking on the hike or students could utilize a plant identification app such as iNaturalist or Seek to identify unknown plants on the trail. They could then use an internet search (or perhaps an informational app) to learn about the plant’s defensive traits. Students can also create their own field guides to identify common plants with defensive traits. They could create this with pen and paper or digitally.

Britta Moore is a science teacher and naturalist living in Lakewood, Colorado, USA with her husband, daughter, and their dachshund, California King Snake, and two rottweilers. She completed her Bachelor of Science in Biology-Zoology and her science teaching post-graduate work at California State University of Long Beach and is a recent graduate from Miami University of Ohio in the Denver Zoo’s Advanced Inquiry Program. She has taught science in K–12 schools for nine years and is building an in-home nature-based, early learning center and a nature-connection program for Colorado families. In her free time, you can find her exploring the natural world.

References:

[1]Wandersee, J., & Schussler, E. (1999). Preventing Plant Blindness. The American Biology Teacher, 61(2), 82-86. doi:10.2307/4450624. Accessed https://www.jstor.org/stable/4450624?seq=1

[2]Balding, Mung & Williams, Kathryn J.H. (2016) Plant blindness and the implications for plant conservation. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cobi.12738

[3]Dugan, F. M. (2016). Shakespeare, plant blindness, and electronic media. Plant Science Bulletin, 62, 85–93.

[4]Kritzinger, Angelique (2018). ‘Plant blindness’ is a real thing: why it’s a real problem too. The Conversation. Accessed at https://theconversation.com/plant-blindness-is-a-real-thing-why-its-a-real-problem-too-103026. Accessed on March 6th, 2021.

[5]Erb, M. (2018). Plant defenses against herbivory: closing the fitness gap. Trends Plant Sci. 23, 187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.11.005

[6]Mortensen, B. (2013) Plant Resistance against Herbivory. Nature Education Knowledge 4(4):5

[7]Colorado Plant Database. (2019). Colorado Plant Database, Colorado State University Extension, Jefferson County. [online] Available at: https://coloradoplants.jeffco.us/plantAbout [Accessed 19 Oct. 2019].

[8]Vernimmen, T. (2019). How Monarch Butterflies Evolved to Eat a Poisonous Plant. [online] Scientific American. Available at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-monarch-butterflies-evolved-to-eat-a-poisonous-plant/ [Accessed 20 Oct. 2019].

[9]War, Abdul Rashid et al. “Mechanisms of plant defense against insect herbivores.” Plant signaling & behavior vol. 7,10 (2012): 1306-20. doi:10.4161/psb.21663

Appendix A: Supplementary Resources

Figure 1. “A plant defense trait reduces the negative impact of herbivores on plant reproductive success. By consequence, on herbivore attack, genotypes carrying the trait (yellow leaves) should increase their fitness (i.e., their relative abundance in the next generation) compared with genotypes that do not carry the trait (green leaves)”.4

Colorado Columbine

|

Mullein

|

Curlycup Gumweed

|

White Sweet Clover

|

Big Root Prickly Pear

|

Silvery Lupine

|

Woods’ Rose

|

Yucca

|

Figure 2. The botany cards above provide information about the defenses of common Colorado plants. They will be distributed to the participants/students (children and their guardians) to read to the group as they encounter the respective plants on educational hikes.

Figure 3. Protective Plant Bingo Cards. These will be distributed to the children as part of a formative assessment to gauge their understanding of the learning objectives.