Celebrating Earth Week: It’s Elemental

By Deanna Fry

Making real and heartfelt connections to nature is crucial for our survival into the next millennium. It is especially important in this age of virtual reality when so many people — children included — have become estranged from the natural environment.

The five-day unit Celebrate Earth Week ’98 is a collection of ideas, activities and resources for recognizing, exploring, honouring and celebrating our connections to the earth during Earth Week from April 20-24, 1998. The unit is organized around five daily themes, beginning with the four natural elements of Water, Fire (Sun), Earth and Air, and ending the week with a celebration of the Spirit of Life. Each day, short thematic excursions outdoors give students opportunities to make connections with these elements in nature, while indoor activities invite exploration of the important roles they play in our world.

The theme days and activities are open-ended suggestions to adapt and extend in any way you like. This is just the beginning. Consider, perhaps, a giant wall chart of the theme days, with their meanings simply stated and students’ work displayed in a prominent place. Daily morning announcements introducing the theme days and concepts is also a nice way to recognize Earth Week in the whole school. In all, simplicity is the key. There is no need to travel far or to be extravagant. We need only to open ourselves to world around us.

WATER (MONDAY)

All living organisms use water in one way or another, and our common need of this important element unites us. We can go many days without food, but not without water. Many people in the world must go to great lengths to collect water and often the water they rely on is not clean. It is important to convey an appreciation for the abundance of clean water we have in North America, and the need to conserve the world’s fresh water supply.

Why not start the water theme by taking your class down to the fountain for a drink? Ask students to think about where the water came from and the route it took to get to the fountain. Back in class, demonstrate how much of the world’s water supply is fresh, clean and potable by using a bucket of water, three one-litre containers and a 10 ml eyedropper. Put 951 ml of water in container A and explain that this represents all the world’s salt water. Put 49 ml in container B, explaining that this represents all the fresh water that exists as ground water, ice caps, glaciers, and water in plants and animals, including humans. Use the eyedropper to put 0.05 ml in container C and explain that this represents all the fresh water in lakes and rivers alone. This concrete demonstration is very effective in stressing the value of clean, drinkable water. Tell them that Canada has about two- thirds of the world’s fresh surface water, that Canadians use more water per person than anyone else in the world and pay the least for it! Allow time for reflection on and discussion of these facts, and the feelings and ideas they may invoke. Do this as a whole class, in pairs using Think, Pair, Share, or in small groups using Round Table Response. Prompt consideration with the following questions:

- Do we value and appreciate water or do we take it for granted? Do you?

- How do we waste water? How do you waste water?

- How can we conserve water? How can you conserve water?

- How do people in other parts of the world get fresh water? Is it freely available?

- Imagine living in a place where fresh water is scarce and has to be carried a long way. How would that change your habits and attitude toward water?

- Will you change the way you use water from now on?

Next, lead younger children in a round of “Down by the Bay” or “Listen to the Water.” Then use simple diagrams to explain the basic hydrological cycle and watershed mechanisms: open body of water, evaporation, cloud formation, precipitation, run-off into streams, rivers and back to larger bodies of water. Have them draw their own versions of the cycle or label and colour one you have prepared.

Next, lead younger children in a round of “Down by the Bay” or “Listen to the Water.” Then use simple diagrams to explain the basic hydrological cycle and watershed mechanisms: open body of water, evaporation, cloud formation, precipitation, run-off into streams, rivers and back to larger bodies of water. Have them draw their own versions of the cycle or label and colour one you have prepared.

Remind older children of the basic hydrological and watershed principles. Point out how wetlands operate as natural filters to purify water and that they are disappearing at an alarming rate due to human development. Discuss the fact that North Americans use water of drinking quality for all their water needs (washing, flushing, lawns and industry), then look at the processes we use to purify water. Demonstrations using sand, charcoal or other materials that function as filters help students see the process at work. Compare the taste of tap water, spring water and distilled water, vote for a favourite, and graph the results.

Go outdoors for a water walk to a nearby creek, stream, lake or puddle. Help the students place this body of water in the larger context of the water cycle discussed earlier. Today is your lucky day if it happens to be raining . . . If a water walk isn’t suitable, take some clean paint brushes and a few buckets of tap water outside. Use them to paint masterpieces on the school wall and notice how the water evaporates once painted on the surface.

Finally, play some relaxing water music, such as recordings of waves, waterfalls, rain or a babbling brook. Have students relax, close their eyes, and think of a special or fun time they had near water, perhaps at a cottage, in a pool or on a beach. Pass out paper and have them draw to the music or share their stories orally before recording them in written, pictorial or poetic form. An excellent finale is to create a class water book or decorate a bulletin board or hallway with the water stories, poems and illustrations.

Other approaches:

- weather and the role water plays in it

- the three states of water: solid, liquid and gas

- aquatic life in salt and fresh water

- fishing and related economic and environmental issues

- human uses of water for drinking, transportation, recreation, industry, hydroelectric power

FIRE (TUESDAY)

The sun and the energy it provides are essential to life on the planet. “Fire” energy from the sun is our basic fuel. It is at the root of the food chain and is the initial source of all of our energy resources.

Begin by reading a story, legend or myth about how the sun came to be, or about the cycle of day and night. Some examples might be the Greek myth of Demeter and Persephone, or stories such as “How Spider Stole the Sun” (Joseph Brushac, Keepers of the Earth) and “Why Birds Sing in the Morning” (Terry Jones, Fairy Tales). Discuss the importance of sunshine in our lives. Brainstorm ideas for new and different versions of creation stories that explain the sun or day and night, and have the students write their own, individually or in groups. Share the results informally, or take the stories through the writing process and publish an illustrated class collection of sun stories.

Songs or other works of art related to the sun are age-old and seem to come quite naturally. To begin, primary students could sing “You Are My Sunshine” or Raffi’s “Mr. Sun,” while intermediate students could be reacquainted with the Beatles by listening to “Here Comes the Sun.” Invite students to create their own artistic interpretations of the sun. Provide a wide variety of materials — paint, paper, yarn, fabric scraps, wallpaper — and display all of the suns together to create a quilt effect on a bulletin board or hallway wall.

Introduce the theme of fire in Math, Science and Technology with a study of ecosystems and the food chain. Begin by showing students an orange and then sharing orange sections or slices (other fruits could be used but do not represent the sun as concretely as an orange does). Tell the students that they are eating the sun, and discuss how this is true: the sun’s energy is made into food for the plant through photosynthesis and stored in the fruit for the purpose of self-propagation. This leads naturally to the concept of food chains in ecosystems: the sun’s energy enables plants to grow, herbivores eat plants, carnivores eat herbivores, and so on. Examine a local food chain to see these principles at work.

Take the students outdoors to make a personal connection with the concept of food chains. Go for a walk around your school community to identify various life forms and discuss how they depend on the sun and one another. (It may be only pavement, patches of dirt and weeds, ants, birds and recess snack leftovers, but it will still create a sense of personal relevance.) As a follow-up to your walk, students can create a pictorial presentation of a food chain. This can vary from a drawing of what they just saw to researching information to map out a food chain. (BioArk is an excellent primary/junior program that explores many of the concepts.)

Other approaches:

- Fire for warmth/cooking/survival: stories of how humans got fire in the first place; the necessity of fire for human survival without modern energy technology; the role of the sun in producing fuels for fire, such as wood and coal (much of the world still relies on these).

- Sun as the basis of the energy chain: stories of life without modern energy technology (pioneers, developing countries); the variety of energy sources, their uses, adaptations and connection to the sun; conservation and future implications of using these resources in the way that we do.

EARTH (WEDNESDAY)

The Earth element is perhaps the easiest for students to connect with because it surrounds us in such a concrete way. We see, smell, feel and hear it, and whether indoors or out, natural or human-made, everything we come into contact with is of the earth.

Begin Earth Day with a creation story which explains how the earth came to be. Such stories, told all over the world, both shape and reflect a culture’s values, attitudes and relationship to nature, often suggesting the stewardship role to be played by humans. Read or tell the Native North American creation story “The Earth on Turtle’s Back,” or “Turtle Island” as it is sometimes known (one variation can be found in Keepers of the Earth). The many animal roles and the repetitive pattern of this story make it ideal for dramatic re-enactment, and primary students love to make masks and costumes as part of the play. Older students may read two or more creation myths from different cultures to compare and contrast their explanations of nature and the blueprints they provide for our role as humans.

Bring the earth focus to the present by going outdoors to explore the school and neighbourhood terrain. Have the students notice what covers the ground and what grows out of it. Try to find a place where the cycle of growth, life, death and decomposition is apparent. This may be a rotting log, a patch of last year’s leaves or even the school composter. Point out the circle of life present in your chosen example: for example, seed, sapling, mature tree, dead tree, fallen trunk, decaying log, soil. Explain that animal remains go through a similar process and this is how death renews life in nature. Point out elements in soil, such as stones, pebbles and sand, the results of rock erosion. You may want to have students collect fallen treasures for an art lesson or pick up a rock to use later for the Dancing Rock Song.

Back in the classroom follow up by writing about, drawing, labelling or colouring a picture showing the cycle of growth, life, death and decomposition. Discuss the human need for and use of the many resources and products of the earth, from plants and animals to minerals.

Planting seeds is a terrific way to extend this theme and make a lasting impression on the students. Chart progress, keep a log of plant growth over time, or use different seeds or soil types for scientific experimentation. April is a great time for classroom planting, and the seedlings started on Earth Day can be taken home later in the season.

End the day with the Dancing Rock Song (see below), a favourite with children of all ages.

Other approaches:

- Explore the geological and human history of the local landscape: soil and rock composition, archeology, history of land use and farming techniques

- Consider the results of human intervention: industrial pollution, landfills, natural resource management

AIR (THURSDAY)

Air is somewhat of a mystery for younger students because it is far less concrete than the other elements. Begin by noticing how air takes various forms and moves other things. Activities like blowing bubbles and making and flying kites, scrap paper airplanes or grocery bag parachutes introduce air nicely, or can provide a good follow-up to a story about the wind, such as Millicent and the Wind (Robert Munsch) or “The Wind Ghost” (Terry Jones, Fairy Tales).

Take students outdoors to notice how air surrounds everything and provides a medium of transport for many things, from human voices to birds and pollen. Circumstances permitting, have students sit or lie back to watch clouds or treetops move with the air currents, and to feel the air playing on their own skin. Point out the carbon dioxide/ oxygen cycle, in which plants provide oxygen for animals, and animals provide carbon dioxide for plants. Remind students that air is just as much a part of our inner world as it is our outer world, that air is at work within them every living, breathing moment of their lives.

Take students outdoors to notice how air surrounds everything and provides a medium of transport for many things, from human voices to birds and pollen. Circumstances permitting, have students sit or lie back to watch clouds or treetops move with the air currents, and to feel the air playing on their own skin. Point out the carbon dioxide/ oxygen cycle, in which plants provide oxygen for animals, and animals provide carbon dioxide for plants. Remind students that air is just as much a part of our inner world as it is our outer world, that air is at work within them every living, breathing moment of their lives.

Back indoors, students may undertake a more in-depth study of topics such as the carbon dioxide/oxygen cycle, air as a transportation medium, or atmospheric considerations such as wind and weather. A creative examination might be to have students write and present poems or raps on the subject.

End the day with relaxation/ breathing exercises or a quiet time with soft, relaxing music, so that students can feel the flow of air inside them. Awareness of one’s breath is a great tool for self-knowledge and self-control, and helps to bring the air message home.

Other approaches:

- Air in relation to weather: atmospheric pressure, clouds, tornados, etc.

- Carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and other gas cycles that go unseen

- Human uses of and impact on air: transportation, air pollution, space travel

SPIRIT OF LIFE (FRIDAY)

Defining and getting in touch with the Spirit of Life can be challenging and elusive. Think of a time when you were out in nature and saw something that made you stop dead in your tracks, spellbound by the force of its uniqueness, strength or beauty. This is an experience of the Spirit of Life, when the part of you that is alive connects with and recognizes a similar part of someone or something else, whether it be having a chickadee land on your hand for a seed, running into an old friend, or watching a beautiful sunset.

Begin celebrating this final theme by recapping highlights of your previous water, fire, earth and air experiences. Ask students to recall whether there was any point during the week when they felt particularly close to nature. Explain that the Spirit of Life is not so much something you think about with your brain, but something you feel in your heart. Give some of the following examples of times when people might feel a special connection with nature: watching a beautiful sunset, closely encountering a wild animal, seeing the morning mist rising in a field, noticing the frost patterns on an icy window, jumping into cold water on a hot summer’s day, smelling the fresh air, finding a special rock on the beach, or even loving a family pet. Encourage students to share their own experiences aloud and follow up with a drama lesson in which small groups enact one of these shared experiences in mime or tableau while the rest of the class guesses what is being portrayed.

End the lesson with a quiet time during which students sit or lie comfortably with the lights dimmed and soft relaxation music playing. Encourage them to breathe deeply and relax their entire bodies, using gentle reminders and positive reinforcement every few moments. Ask these questions, pausing between each one, to extend the exercise into a creative visualization:

Imagine you are in a beautiful, natural place that you love right now. What is it like? What is the land like — flat, hilly, mountainous? How does the air feel — is it hot or cold, dry or damp? What colours do you see there? What sounds do you hear — the wind blowing, water flowing? Are you alone? Are there animals, trees, plants or flowers? How does it feel to be there?

Allow time for the students to explore the inner world they have created. Then slowly guide them back to their immediate surroundings by having them wiggle their fingers and toes, hands and feet, arms and legs and, finally, stretch their entire bodies. Depending on how the session went, you may want to give students time to express their visions orally or through drawing or writing.

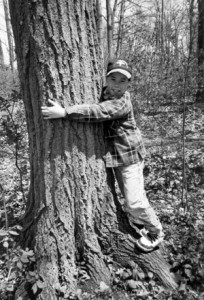

Make the last outdoor excursion a celebration of all that has been learned during the week. Encourage the children to see the interconnnectedness of water, fire, earth and air — that all living things on the planet are united in their need for these elements. Use all of the senses to notice and appreciate whatever nature provides in your surroundings. Breathe deeply, and remind students that we breathe the same air expired by plants and exhaled by animals. Hug a tree, watch the clouds, count some birds or ants, smell the grass and the earth beneath it. Take a micro-walk by following a metre-long piece of string finger-by-finger on hands and knees, perhaps with a magnifying glass. Use your imagination on this final walk outside and let the spirit move you.

Back indoors, conclude by brainstorming or webbing all the life forms noticed on the walk. Have students consider the roles that water, fire, earth and air play in life on this planet. An Earth Week jigsaw might be a fun way to wrap up. Allow time to reflect on all that has been explored and discovered during this celebration of Earth Week ’98, and urge your students to continue to make these important connections to nature for the rest of the year — and the rest of their lives.

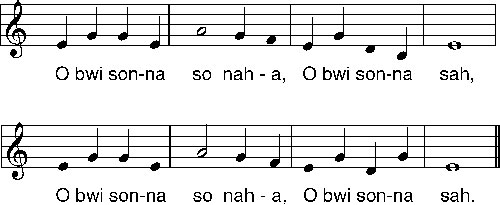

The Dancing Rock Song

Instructions: Everyone sits in a circle on the ground and places a medium-sized rock in front of them. Teach the song first. Then add a clap on the “O”s. Then tap the ground on “O” and the left knee on “so” and “sah”. Then tap the ground in front of you and the ground in front of your neighbour to the left. Last, pick up your rock on “O” and set it down in front of your neighbour on the left on “so/sah”. The rocks will dance around the circle.

Deanna Fry teaches grade two and directs The Green Group environmental club at Lakeside Public School in Ajax, Ontario.

This article was originally published in GREEN TEACHER, Issue # 53, FALL 1997, pp. 23-27. This article may be photocopied for use in the classroom or for sharing with colleagues. It may not be reprinted, in whole or in part, in any publication without permission from the editors of Green Teacher magazine.

Resources:

Bruchac, Joseph, and Caduto, Michael. Keepers of the Earth. Saskatoon, SK: Fifth House Press, 1991, and Keepers of the

Animals, Saskatoon, SK: Fifth House Press, 1991.

Caduto, Michael. Earth Tales from Around the World. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 1997, ISBN 1-55591-968-5.

Jones, Terry. Fairy Tales. Markham, ON: Puffin Books, Penguin, 1981. (Terry Jones is a member of the Monty Python team. His

modern fairy tales deliver their message with a humourous twist.)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.