The Story Model: Empowering students to design their future

By Susan M. Drake and Joanne L. Reid

Will the post-pandemic world return to a past version of itself or will there be a new story with changed values? The Story Model (Drake et al., 1992) is a transdisciplinary way for students and teachers to explore these questions, and address change and the “unimaginable” future. At a time of deep uncertainty, it is crucial to offer students two things: an approach to interpret the world they live in now, and a way to nurture their hope and personal agency for their future.

The new story for education

No matter what changes, two fundamental questions of education will remain: What is important for students to know, do and be in the 21st century? And how is education best delivered? We cannot reliably predict the “know” of essential content, but it’s clear that artificial intelligence will play a role (Hey, Siri).

What should students be able to do? There is general global consensus that learning 21st-century skills is essential (OECD, 2020). The Canadian Ministers of Education identify these skills as:

- critical thinking and problem solving

- innovation, creativity, and entrepreneurship

- learning to learn/self-awareness and self-direction

- collaboration

- communication

- global citizenship and sustainability.

How do we want students to be? While attitudes, values and behaviour are influenced by cultural norms, in Canada we want students to develop a good work ethic, and to be flexible, open-minded and committed to being good citizens.

How is the curriculum best delivered? In a post-pandemic world, we anticipate an expansion of technological skills, integrated curriculum, project-based learning, design thinking, and personalized and collaborative learning.

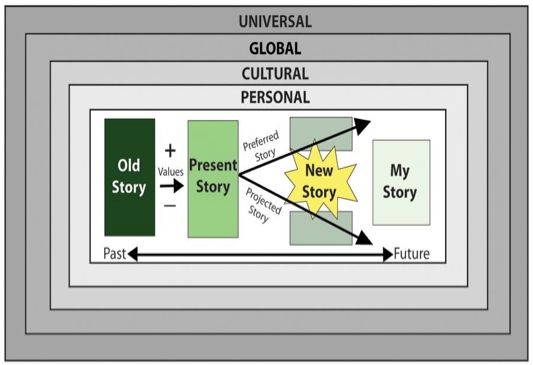

The Story Model (see Figure 1) is aligned with our view of future education and can be integrated into curriculum in any subject area. It is the perfect vehicle for a collaborative multidisciplinary project and is particularly useful to explore “wicked problems.” The UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (https://sdgs.un.org/goals) are examples of wicked problems. Ending poverty, achieving zero hunger, and addressing climate change are problems so complex and intertwined that they can seem overwhelming and unsolvable. The Story Model’s emphasis on individual and collective agency for positive change counters despair and motivates action in the face of such problems.

Figure 1: The Story Model Framework.[1]

Storying for meaning

Humans make meaning through narrative (Binder, 2011; Vygotsky, 1978). Individuals “story” their lives to make sense of them, interpreting experiences to create a story that has a perceived past and an anticipated future. Groups, cultures, and nations also have stories. Stories are filled with emotion and conflict. Embedded values influence decisions. The Story Model makes these stories and values explicit. Alone or collaboratively, people can consciously choose to change the storyline if they do not like its direction. We can create a new story to live by.

Applying the Story Model

- Explore a topic. Students work with the Story Model graphic (Figure 1) to explore a relevant, engaging topic through the four interwoven layers that frame the model: personal, cultural, global and universal. Topics such as pollution, the Olympics, beauty products, hockey, video games, and racism can be studied at different levels of complexity throughout the grade spectrum. Let’s use the topic of blue jeans to consider each frame.

The personal narrative is the first lens of knowing. Canadian students, familiar with this popular fashion item, can write or tell a story about wearing or wanting to wear jeans. A personal connection increases engagement and highlights the relevance of the topic.

The second lens is the cultural story. Each student lives within at least one cultural story, be it ethnic, religious, social class and so on. Some cultures may disapprove of jeans, whereas jeans are almost a uniform in others. Critical reflection helps deconstruct these cultural stories and their often taken-for-granted values.

The third lens is the global story. The popularity of blue jeans has significant global repercussions for ecology, labour, and the economy, to name a few. Cotton cultivation and manufacturing consume vast quantities of water, produce toxic pollution and exploit labour. Multinational companies advertise, transport and sell globally. When Canadians purchase their jeans at a local mall, they tap into a huge international network worth $100.25 billion US in 2020 (Shahbandeh, 2020).

The universal story connects us as humans. We all experience human needs and hold values. Humans everywhere value survival, health, and social belonging (Maslow, 1954). Yet, these universal human rights are threatened by the fashion industry.

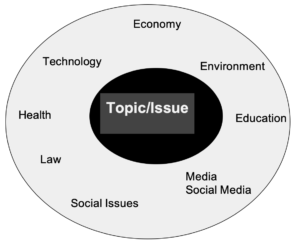

- Analyse the present story. Individually or in groups, students analyze the present story of their topic(s) by situating it within a transdisciplinary real-world web (Figure 2) that has been designed by the teacher, the student or both together. The categories on the web are flexible; for example, the web in Figure 2 is missing politics/ government, global connections and the arts. Perhaps they would appear on the web you designed. The key idea is that categories are broad and rooted in real-world context. For younger children, the web would contain fewer words and words that are more familiar to them. For example, the word economy becomes money; equity becomes fairness; law becomes rules; technology becomes computers.

An effective web ultimately pushes any topic into the global realm. It also extends any topic from a disciplinary to a transdisciplinary context. Students use each category on their web to identify what they already know. They supplement their knowledge with research. Frequently, they consult with other students to make connections among categories. Systems thinking can be made visible by drawing connecting lines on a paper transdisciplinary real-world web or mind-mapping on the computer. Completing this exercise shows that in the real world, every category on the web is interconnected.

Figure 2: Example of a transdisciplinary real-world web

- Identify the old story and its values. Next, students consider the present story in light of the past, their personal stories and the transdisciplinary real-world web. The present story contains elements of the past. What are the historic roots? What explicit values of the old story persist? Old story values of the jeans story would include industrialization and capitalist values. Are there positive parts of the old story that are still useful? For example, students might enjoy the comfort of jeans. However, learning that their manufacture has environmental repercussions and economic disparities invites critical thinking.

- Creating Create a new story. Applying the Story Model graphic, students envision different futures. The model proposes two (or more) divergent paths for the future: either a projected story as a continuation of the old story or a preferred story as an imagined idealized alternative. The projected story would continue an industrial worldview with values such as profit, competition, greed and power. The preferred path will be an idealistic (and possibly unrealistic) story. This path might include eco-friendly manufacturing, and safe, secure working conditions based on different values such as sustainability, social justice, collaboration, and empathy.

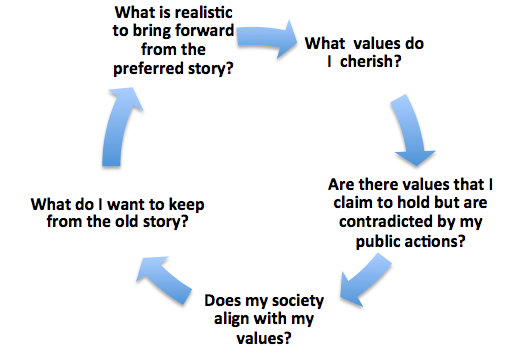

Students critically evaluate the old and present stories and look for ways to reconcile them with their idealistic future story. The future story needs to consider the interdependence of multiple categories in the dynamic, transdisciplinary real-world web. Creating a new story evolves in an iterative, creative way, focused on interwoven questions (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Creating a new story

The new story is not an either/or choice; it is more of a selective synthesis, a “both/and” resolution. Martin (2007) defined this process as integrative thinking – generating a solution that contains elements of the opposing ideas but is superior to either one. Central to the process is the question: “How can we accomplish [this] while also accomplishing [that]? As students grapple with a possible answer, more and more complications arise. The question “but what about…?” always defeats a simple, superficial solution.

Returning to the blue jeans example, one tension between seemingly opposing positions is profit versus health. How can we have a thriving denim/blue jeans industry while also having a healthy environment and healthy workers? The resolution must resolve around a collective and sustainable option, which is what we are seeing with the green initiatives (water reuse, fair wage practices, use of natural dyes) of major companies that have responded to collective consumer activism (See Farra, 2020; Sarkar, 2020).

- Committing to “my” story. As a “final” step, students develop a values-based personal action plan to actualize their new story. They might purchase sustainably made jeans, endorse eco-responsible companies on their blogs, repurpose used denim and so on.

Education (research, schools), media, and legislation propel a new story forward. The seatbelt is a good example of a formerly new story that is a taken-for-granted one today. The acceptance of seatbelts happened when people learned how they enhanced personal safety and when laws were created to penalize people who did not wear them. Emerging new stories are LBGTQ2+ equity, integration of AI, legalization of marijuana, and mainstream adoption of alternative power sources.

A new story does not stay “new” for long; it becomes the status quo from which another new tension arises. Thus, students come to understand the importance of lifelong reflective critique of the status quo. In an uncertain world, they see that action is the antidote for despair – – that the individual has influence. Look at Greta.

| Adapting the Story Model for Younger Students The model can be simplified in multiple ways and combinations to suit various ages. Focus only on the inner part of the model shown in Figure 1 to emphasize past, present and future. For example, the evolution of the car is one such story. Focus only on the concentric frames to explore the personal stories and values embedded in a topic. Focus on the whole model to explore changing values over time. For example, John A. Macdonald was considered a national hero according to values of the past, yet todayy, he is critiqued for his racism. The controversy over his statues reflects the conflicting personal and cultural values of past and present. Students can reflect on their own values to make their own decisions. Focus only on the web to emphasize interconnections among categories or disciplines. For the richest experience, apply both the Story Model and the web; students can follow specific steps to move from “old” to “new” story. |

| A Grade 9 Case Study To learn how the Story Model was used in Grade 9 Science Class, read the article “A New Story in Grade 9 Science,” by Susan M. Drake, Bruce Hemphill, and Ron Chappell: https://greenteacher.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/A-new-story-in-grade-nine-science.pdf |

References

CMEC. Global Competencies. www.cmec.ca/682/global_competencies.html

Drake, S.M., Bebbington, J., Laksman, S., Mackie, P., Maynes, N. & Wayne, L. (1992). Developing an integrated curriculum using the story model. OISE Press.

Binder, M. J. (2011). Remembering why: The role of story in educational research. In educationEducation, 17(2). https://ineducation.ca/ineducation/article/view/82/357

Farra, E. (2020, April 24). These are the 10 sustainable denim brands you should know about now. Vogue. www.vogue.com/article/best-sustainable-denim-brands

Martin, R. (2007). The opposable mind: How successful leaders win through integrative thinking. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

OECD. (2020). OECD Future of education and skills 2030. www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/about

Sarkar, P. (2020, July 29). Making denim & jeans [in a] more sustainable way – initiatives by top apparel brands. https://www.onlineclothingstudy.com

Shahbandeh, M. (2020, Dec 2). Global denim market – Statistics & facts. www.statista.com/topics/5959/denim-market-worldwide

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Note:

[1]Adapted from Drake, S.M., Bebbington, J., Laksman, S., Mackie, P., Maynes, N. & Wayne, L. (1992). Developing an integrated curriculum using the story model. OISE Press.

Susan M. Drake is a Professor at the Faculty of Education, Brock University. Her research involves integrated and transdisciplinary approaches to curriculum and narrative research.

Joanne L. Reid’s research on curriculum design and assessment builds on many years in classrooms and in professional adult and large-scale assessment programs. She is interested in innovative practices that contribute to student engagement and equity.