Turning Rotten into Right: A Kindergarten Study of Decomposition

Originally appears in the Winter 2013-2014 issue

Decomposition is a rather unsightly natural process, but it is an essential one. At its core, decomposition enables dying organisms to return their nutrients to the earth for re-use; a truly beautiful part of the life cycle. Children know from experience that fruits rot and garbage stinks. My colleagues and I aimed to harness the powerful sensory experiences children have towards decomposition into learning by creating a year-long curriculum that took the “eew” factor into the “Aha!” zone.

My colleagues and I wanted to create a hands-on interdisciplinary Kindergarten curriculum by weaving important scientific concepts with language arts, social studies, art, music, and technology. We also wanted to entwine the curriculum into the daily life of Kindergarten so that children could revisit the same practices and concepts throughout the year. By studying natural and managed decomposition as a part of everyday life, we encouraged young children to reflect on their own relationship to waste and its impact on their environment in a very personal way.

Classroom Routines

In September, as the children enter Kindergarten, they become familiar with the rhythms and routines of our classroom. One of the first things they learn is that there are four receptacles for their waste: a paper recycling bin for paper, a co-mingles bin for glass, metal and recyclable plastic, a food scraps bucket for certain types of food and paper towels and a garbage can for what can’t be put in the first three. Our goal, I tell them, is to keep the garbage can as empty as possible.

Jobs are assigned on a weekly basis and two Environmental Stewards are responsible for taking the food scraps bucket out to the garden and emptying the contents into the outdoor composter. Most children know that food “goes bad,” so I tell them that putting it into the composter is a way of helping the food recycle back into the earth. The words compost, composter, recycle and environmental steward become a part of their daily language. I show the students a rap about composting sung by some wiggly worms, which quickly becomes a favorite YouTube video at lunch!

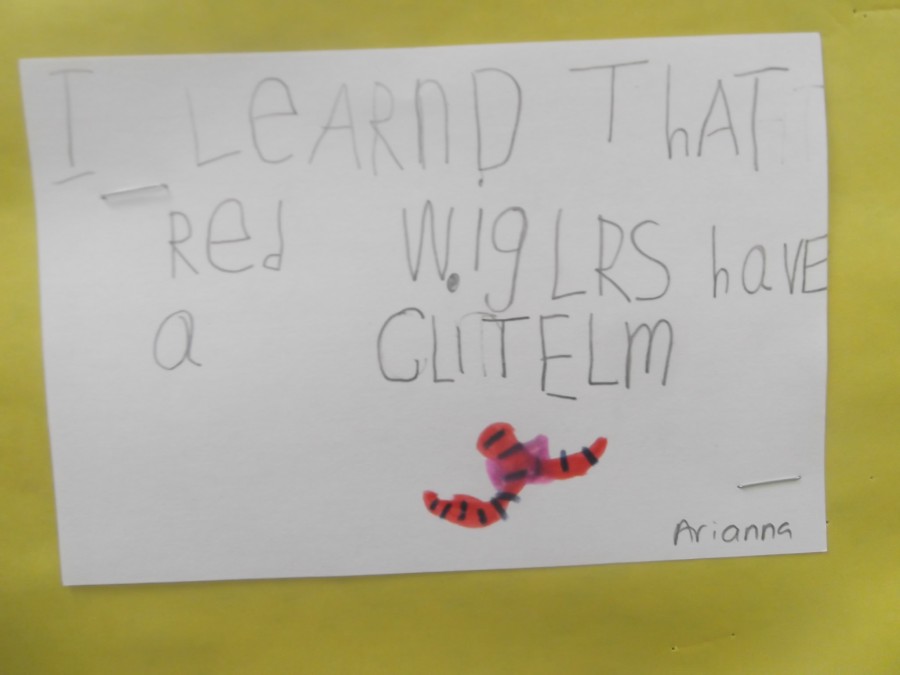

Our Class Pets, the Red Wigglers

We soon introduce the children to our class pets; Eisinia Fetida, or red wiggler worms. Our worm bin is brought into the classroom in the mornings so that children can dig into the bedding and investigate the worms and their home. The children help with cutting fruit and vegetable leftovers from our snacks and lunches and feeding it to the worms, and tear newspaper strips to refresh the bedding. They learn that the worms are recycling the food by eating it and that what looks like soil in the bin is actually worm poop, or as they learn to call it, castings.

In addition to seeing worms in the worm bin at different stages of growth, my students also come across other living organisms, like snails, nematodes and mites. I introduce the word ‘decomposers,’ explaining that all these organisms are helping to break down the food we are putting in the bin.

Later in the year, I present a formal lesson on worm anatomy and a worm’s role in enriching the soil. The children use their experience with the worms to express what they have observed and use this to build their conceptual understanding. We give them the accurate scientific terminology and they use it with great enjoyment. We provide them with opportunities to investigate the worms more closely with magnifying glasses and powerful microscopes, which they use to identify body parts and observe the worm’s movements. Students are asked to figure out “Do worms like water?,” “Do worms like light?,” and “Do worms move forwards or backwards or both?”

Garden Work

While the children familiarize themselves with the worms, they are also introduced to outdoor garden beds. In the garden, the students’ senses are excited by herbs, pumpkins and other plants that they can smell, touch, pick and taste. They learn how to weed and mulch. Later in the year, they harvest compost from the outdoor composter and the worm bin to mix into the beds and indoor plantings.

The garden is a great place to dig for earthworms —comparisons with the red wigglers’ anatomy are inevitable— and I point out they can see some other fascinating creatures by turning over a log.

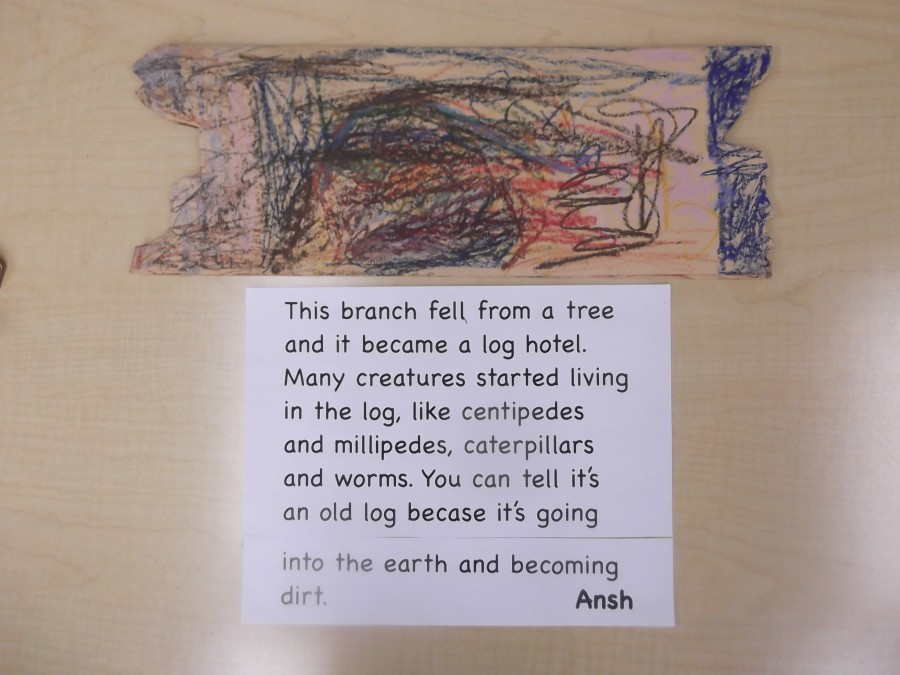

Nature Walks and Log Hotels

We start our nature walks in September, in the woodlands adjacent to our campus. One of my favorite walks to go on is the one with our 4th grade buddy class. The 4th graders share what they have been studying about “log hotels”: a decaying log that can house many different species. Immediately, the kindergartners start comparing what they see in the woods with what is under the log in our garden.

In the classroom, I set up a temporary log hotel for observation and exploration. Students start to identify and name the different creatures they see, looking for invertebrates, arachnids, insects and gastropods. We read books on log hotels and discuss the life cycle of a tree. Even a dead tree that has fallen down continues to be a source of life for other living things. Decomposition comes up again as we discuss how the living organisms that live in this tree eventually break the tree down back into the soil.

The children belt out the FBI song (Fungi, Bacteria and Invertebrates) by the Banana Slug String Band; a fun musical tool for learning about nature’s recyclers.

Through the seasons, nature walks continue to be an excellent avenue for children to observe natural decomposition. As we trudge through fall leaves and investigate fallen trees, the evidence of decomposition is all around us.

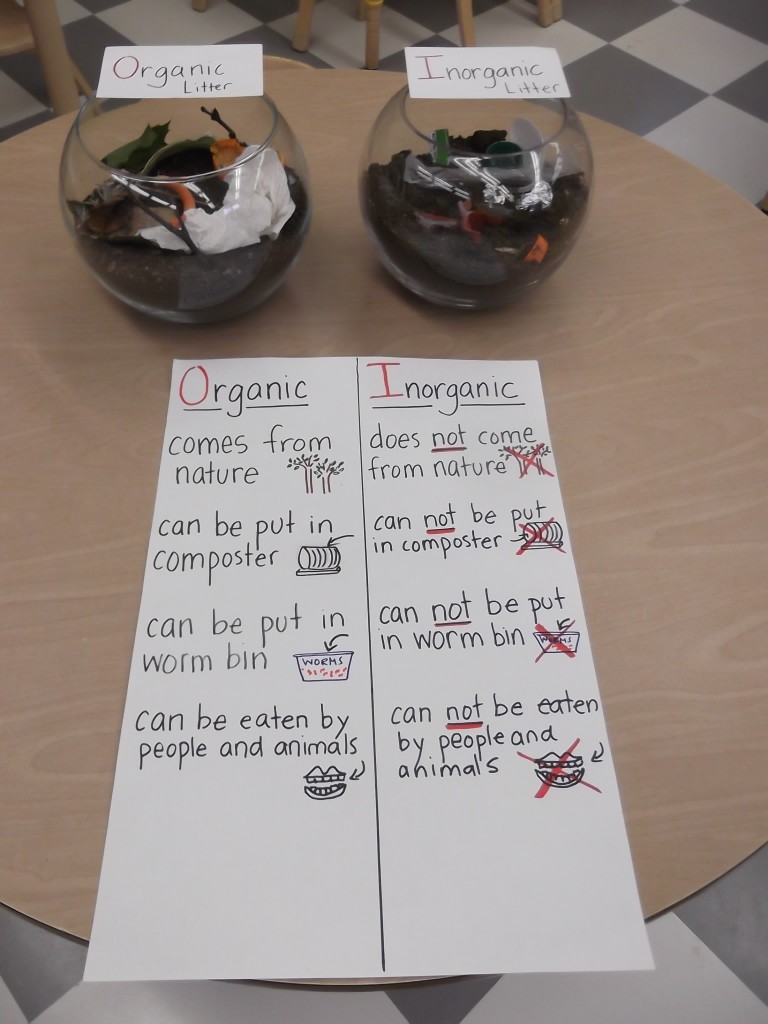

Organic and Inorganic Litter Study

Around mid-October, we add on another layer of our decomposition curriculum. All of the trash from the day’s lunch—apple cores, banana peels, Ziploc bags, juice boxes, napkins and some added leaves and twigs from the playground—is put on a tray.

We play “What’s the Rule?”: as I place the litter in two different trays, the children try to figure out what rule I am using to separate the litter. It’s always fun to listen to how they start narrowing it down, starting with “things we can eat/things we cannot eat” to “made in a factory/grown in the garden” and so on. At the end of the exercise, I introduce the words organic and inorganic and we clarify the difference.

I bring out two glass bowls filled with soil — mini-Earths. I fill each bowl with a different type of litter and the children predict what they think will happen to the litter. Some examples of predictions include:

• “they both will stay the same”

• “they both will sink into the soil”

• “the organic litter will get rotten”

• “the inorganic litter will get smaller”

For the rest of the year, the children observe the organic and the inorganic litter, confirming or refuting what was predicted. Inevitably, we keep adding to the mini-earth with the organic litter as the litter decomposes. The mini-Earth with the inorganic litter, however, gets full very quickly and for the rest of the year remains exactly the same: a small but powerful visual.

Throughout the year, we continue to provide opportunities for children to practice sorting our litter and identifying organic vs inorganic, whether we are out in the woods, in the classroom or in our garden.

Bottle Cap Recycling

The Kindergarten classrooms also partner with Aveda, a company that recycles bottle caps. Starting in September, the children bring in bottle caps from home and throughout the year, they sort, count, and collect. As each collection box gets full, we finally mail them off to Aveda. I put some caps into the mini-earth with the inorganic litter and with each passing month, the children note that the caps not only do not decompose but in fact stay exactly the same, crowding the space. They can literally see the difference they are making every time we ship off a box of 2000 caps (yes, we count them!) to Aveda for recycling instead of throwing them in our garbage and sending them off to landfills.

Pumpkin Study

Our Halloween pumpkin study is another fun activity in our decomposition curriculum. After Halloween, the pumpkin is placed in the dirt outside our classroom doors. Every day as they run out to recess, the children check on the pumpkin to see the state it is in. Photographs are taken and kept in their science journals. We compare the pumpkin’s changes to what we have seen happening to the organic litter and to the food in the worm bin. ‘Decomposing’ becomes a regular addition to our daily vocabulary.

During this observation, we go back to the list of predictions they had made before we put the pumpkin out and we check off those that we see are coming true. We note what observations did not pan out, such as “it is going to get bigger.” We also note that many of the predictions yet to occur —“it will turn into soil and make more pumpkins”—are part of the lengthy process of decomposition.

The observation of the pumpkin becomes child driven, as each day, at least one child comes running to a teacher to update us on the status of the pumpkin, or to remind us to take a picture of the pumpkin to add to our timeline.

On cold winter days, we bring the decomposing pumpkin inside so children can take a closer look at some of the decomposers at work. Fungi, of different variety, usually abound. A centipede or a beetle will hurriedly crawl out. The children are immediately assailed with the smell of decomposition as well as the sight of rotting food. Despite the few “gross” and “eew” remarks, the children continue to exhibit scientific behavior in the way they investigate the pumpkin, using magnifying glasses from the science center to take a closer look.

My students are always amazed at how long the stem takes to decompose — long after the rest of the pumpkin is already part of the soil, the stem hangs around stubbornly refusing to go anywhere. When it finally does, one spring day, it is a cause for celebration and an opportunity to count how many days it has taken the stem to finally become a part of the soil.

Making Connections

Once, as we prepare to add some red pepper leftovers to our “organic” mini-earth, one of my kindergartners said, “Ms. Gopal, I think the stem of the pepper is going to take longer to decompose than the soft part.” I pointed out to the class that Savannah had made a hypothesis and asked for her reasoning. She immediately replied, “Do you remember how long it took the stem of our pumpkin to decompose?” Here was scientific thinking based on extrapolation from previous data! Along with such anecdotal evidence, we also use journal entries and representational drawings to encourage children to document and share their understandings or observations.

One day, we tasted brussel sprouts (as part of our weekly taste tests connected to our letter study). We place the leftover chopped brussel sprouts from a taste test into the organic mini-Earth. I decide to add a whole one as well and ask my students to predict if one or the other would decompose faster and why. They record their predictions into their science journals and in the process, I was able to see that most of the children immediately picked up on one of two attributes to explain their reasoning; either the size of the sprouts or the consistency of the sprouts. A couple of children were not sure what would happen – they needed more experiences with decomposition and more time to make the connection.

For documentation and assessment, we use a website called Voice Thread that enables users to add images or videos that other users can comment on by either audio or text.

It is especially effective for young learners whose expressive language exceeds their writing abilities. “I See, I Think, I Wonder,” a Visible Thinking strategy tool developed by Harvard’s Project Zero, is another excellent tool to help determine what connections and conceptual understandings students are developing.

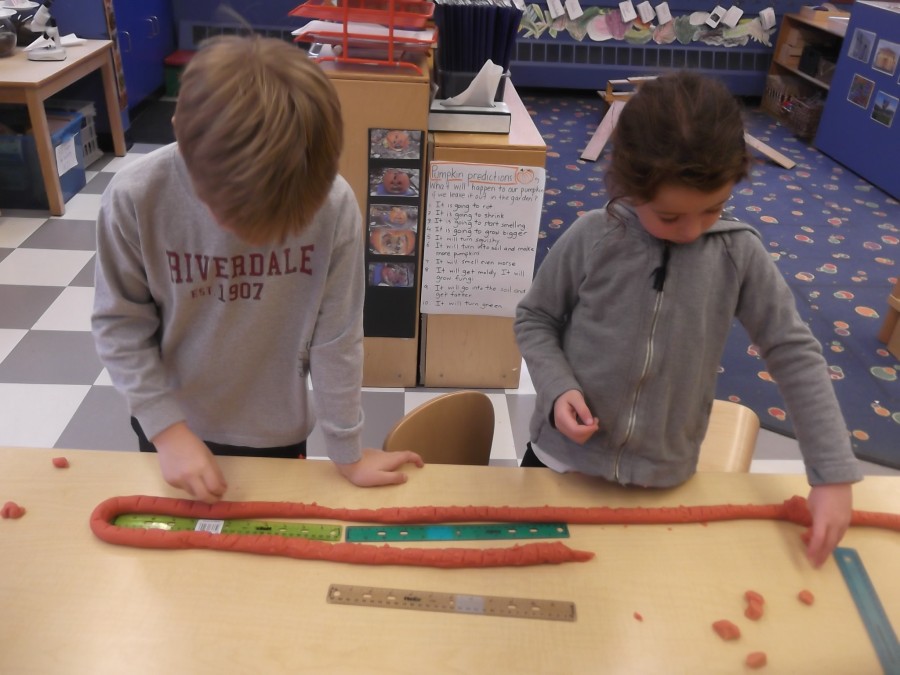

Art projects set up throughout the year (mixed media collages, tempera painting, cray pas murals, botanical sketches and work with clay) provide opportunities for artistic representations of the children’s experiences and knowledge. Making a life-size replica of the Giant Gippsland worm out of play dough brings it to life as does becoming a Giant Gippsland worm when making a line to go to Music.

Environmental Stewards

Through this year-long study, the children start to learn that they can make an impact on their environment, in both positive and negative ways. They begin to make the connection between the kind of litter they throw away and the possible impact it may have on their surroundings. They learn that they can make a difference whether in recycling bottle caps, composting or being on litter patrol. They are more aware of using containers that can be reused or recycled. They learn that even the smallest creature has a deeply important role to play in the health of our planet. Some of my students internalize this, others develop a beginning understanding and still others may need more experiences to continue them on this journey. Regardless, it is a journey that is well worth it at this early developmental stage and which I hope, sets them on a path of both scientific inquiry and respect for the environment.

To view the photo-rich magazine version, click here.

Jyoti Gopal is a Kindergarten teacher at Riverdale Country School in the Bronx, New York.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.