Fracking: Unlocking the Great Debate

Originally appears in the Fall 2014 issue

The use of hydraulic fracturing or fracking has grown considerably more popular in the past decade. As extraction of diminishing traditional reserves becomes more expensive, the technique has been “credited with spurring an oil and gas renaissance across North America, unlocking billions of barrels of oil and trillions of cubic feet of gas.” The allure of gaining access to reserves of natural gas estimated to meet our projected energy needs for the next 100 years, carries considerable weight in political and economic camps. Conversely, the potential health and environmental risks associated with unconventional methods of drilling have served as a rallying cry for fracking’s opponents.

The intense debate over fracking can be framed as an epitome of the struggle or tension between contrasting worldviews: environment/economy, short-/long-term, biodiversity/monoculture. Arguably all oversimplifications, but indicative of the chasm between conflicting positions. If an essential challenge of meaningful education is to deal with controversial issues, the polarizing nature of the fracking debate provides potential for rich, multi-faceted student learning opportunities. It is time to enter rough waters and examine the elements of the controversy, the arguments used to both support and oppose the practice.

This article offers a self-contained instructional unit for a critical analysis and evaluation of the practice of fracking: basic information about the process, the potential benefits and dangers, and a framework for media analysis of the issue, along with resources for use in a high school classroom.

What is the process of hydraulic fracturing?

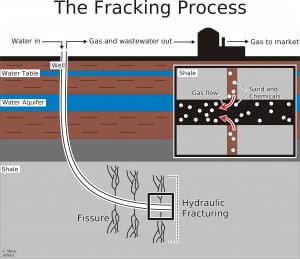

Fossil fuels account for 81 percent of the current global energy supply.[i] Vertical hydraulic fracturing (pumping fluid into existing oil and gas wells) has been used since the 1940s, while the horizontal technique became widespread in the 1990s.[ii] The latter involves drilling vertically downward toward a gas-bearing rock formation and then curving the well in a horizontal direction deep within the rock formation. Horizontal drilling “actually costs 80 percent more than vertical drilling, but it increases efficiency by 400 percent,” thus the technique has been a boon to oil and gas companies. The recent expansion of hydraulic fracturing extracts natural gas from harder to access unconventional sources trapped in rock formations such as shale gas, coal bed methane and tight gas. Millions of litres of water and thousands of litres of chemicals are injected underground at a high pressure in order to create fractures in the rock allowing gas to flow up the well.

An Internet search will easily find a variety of videos ranging from basic steps in the fracking process to more complex, intricate details. As in selecting any material for classroom use, the teacher should be cognizant of the source. The two videos suggested in the Resource section at the end of this article for example, have similar content as to the steps involved in the process, but they are noticeably different in emphasis and perspective towards the benefits and dangers associated with fracking.

After viewing selected videos, the steps involved in the process can be traced with students using the diagram to the right.

Arguments for and against fracking

The potential impact of fracking has significant consequences, regardless as to whether one supports or opposes the technique. The corporate arguments purport increased reserves of energy, high-skill jobs and government revenues, low energy prices and a “cleaner bridge” fuel as the world moves towards less-damaging, renewable sources of energy. Conversely, the associated risks of fracking include increased greenhouse gas emissions, damages to the natural environment, waste and contamination of water, and an assault on aboriginal rights. The lines drawn are clearly antithetical: proponents claim “the waste water generated in the process can be disposed of or treated safely; opponents say run-off, industrial accidents and cost-cutting make contamination inevitable.”[iii]

A plethora of material from both proponents and opponents to hydraulic fracturing is available online. Check out ProCon.org for examples from both sides.

A deeper opposition contends that hydraulic fracturing is being grasped as a means of buttressing an ailing growth economy that is the root cause of many of our social and environmental woes.

There are arguably traces of truth in positions espoused by both camps. It is not unusual for controversial issues to exhibit “gray areas”. Evidence can be put forth to support various positions along the continuum; from the corporate, business-as-usual development perspective to the environmentalists who advocate the total banning of hydraulic fracturing as the only defensible option. A teacher’s challenge is to facilitate a learning process through which students can assess and critique the best available information upon which to reach an evidence-based decision on the wisdom of fracking.

Fracking in the Classroom

Gathering Information

Divide students into five groups, each to research one of the following dimensions/impacts of fracking and then present a summary of the findings to the class. (The structure of this activity complements a New York Times series which provides extensive information about natural gas issues.

- Economy: Identify the economic opportunities, including jobs and revenues for government, and implications for local businesses.

- Land: Explain the effects of fracking on the landscape: including pipelines and large vehicle traffic in the community. Explore whether or not local governments can regulate fracking in their towns.

- Water: Describe the amount of water required for fracking, where the water comes from, and how the volume compares to other uses. Also explain measures to guard against drinking water contamination.

- Waste: Explain the types of waste produced by fracking, including radioactive material, what processes produce the waste, what happens to it and how it can be recycled. Explain the requirements to disclose the chemicals used in fracking.

- Air: Address how natural gas development affects air quality, including greenhouse gas emissions and health problems.

Coming to Grips with Controversy

Pat Clarke’s “How to teach controversial issues” provides a four-step approach to deal with hot topics. His “demystification” strategy can be applied to the discussion around fracking.

- What is the issue about? To identify the nature of the controversy, students consider whether the issue is about values (Is fracking an acceptable means of accessing fossil fuels?), information (Are there disputed “facts” about the impacts of fracking?) or concepts (Is the controversy a matter of definition?). Students will most likely conclude that fracking is mainly an issue about values and information, although the degree or emphasis may vary.

- What are the arguments? To determine exactly what is being said and whether there is adequate justification for the claims being made, students should ask if the conclusions presented in the argument are reasonable, given the information? The fracking debate is fueled by assertions that are contestable. Students will be challenged to distil the competing claims in terms of the available information and the degree to which the respective conclusions are reasonable. The application of two criteria, whether the position is moral (how all people will be affected) or prudential (how it will impact me or my group) should prove insightful.

- What is assumed? To determine the validity of a position, students examine the assumptions behind the argument, including the “voice” of the position. Are vested interests involved? Do the people advocating for/against fracking stand to receive financial or other benefits, depending on the outcome?

- How are the arguments manipulated? To help judge quality of the information, students must determine how an argument is being manipulated: whether claims appear to be supported by evidence or twisted to suit the position. Given its current profile, fracking offers prime opportunities for media awareness; students can examine coverage of fracking with respect to how the media can both reflect and create reality.

After analyzing the arguments and scrutinizing the assumptions, students will be better prepared to make a personal judgment on the issue.

Seeking and Sharing Perspectives

Students are randomly assigned to groups of three to four, and given a personal perspective from which to formulate a position on fracking:

- Property owner of a field identified with potential for fracking

- Mayor of the town, which anticipates revenues from royalties

- Gas industry executive

- Unemployed oil rig worker

- Environmental advocate

- Parent of two young children

- First Nations/Native American chief on an adjacent reserve

- Retiree in a low-income apartment

One student from each group then shares with the class the group’s position on fracking based on how their character would react.

Let’s Debate Fracking … Town Hall Style

Background: A recent series of tests have confirmed a significant reserve of natural gas within the municipal boundaries which can be extracted by fracking. The potential benefits and associated risks of the process have been the talk of the town for several weeks. The town council, itself divided on the issue, has scheduled a “town hall debate” so that concerned citizens can hear the different positions and help make a decision. The resolution being debated is that “Fracking should be banned in _____________ (our community).”

To prepare for the Town Hall Debate

- Student-citizens may be asked to vote by secret ballot on whether they support or oppose the resolution prior to starting. Are they for or against the banning of fracking? The teacher records the results of the vote.

- The class is then randomly divided into two groups, the affirmatives and the negatives. Students then do research to substantiate their respective positions. Each “side” selects two or three representatives to serve as debaters.

- To ensure the debate stays civil and that all debaters have a chance to participate, a moderator should be in charge. The teacher may assume the role or select someone else. S/he will:

- ask questions of participants in an organized manner.

- set a time limit for responses, allowing enough time for all questions to be asked.

- receive and review all questions for the debaters at least two to three days prior to the event.

- discuss the town hall debate format with the participants, outline the topics and issues that will and will not be discussed.

- tell the debaters what predetermined questions will be asked by the moderator and that additional questions will be asked by those in the audience.

- run through all predetermined questions prior to taking questions from the audience to keep the debate on track and ensure all major topics and issues are covered.

At the conclusion of the debate, the class votes again whether or not fracking should be banned. A comparison of the pre- and post-debate vote results will indicate the degree to which public opinion in the classroom may have changed on the issue.

From Knowledge to Action

The rapid development of unconventional sources of oil and gas continues to generate controversy and media attention, particularly in Canada, the US and the UK.

As Neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Yang-Ming once put it: “To know, and not to act, is not to know.” As students learn more about hydraulic fracturing and its associated pros and cons, they may be moved to act, and engage in the process to impact decision-making in their community and beyond. Actions can range from doing more research, to joining green/environmental groups, to lobbying political leaders. Depending upon classroom-specific factors (such as student interest, curriculum linkages, and available time), the fracking issue lends itself to more expansive and intensive treatment. Aspects having particular relevance include: climate change denial, peace, development, human rights, disaster risk reduction and gender connotations.

To view the photo-rich magazine version, click here.

Bert Tulk is a Director of Sustainability Frontiers (www.sustainabilityfrontiers.org), a not-for-profit international organization with offices in Canada and the United Kingdom. Based in Halifax, Nova Scotia, he has been Superintendent/CEO of the Atlantic Provinces Special Education Authority (APSEA) since 2005.

[i] Peduzzi, P. and Harding Rohr Reis, R., Gas fracking: can we safely squeeze the rocks?, Environmental Development, 2013, vol. 6, p. 86.

[ii] Chivers, D. Fracking: the gathering storm, New Internationalist, December 2013, p. 3.

[iii] Bozzo, A., Fracking called both a savior and a scourge, NBC News Business, 21 June 2012.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.